The Book You've Never Read That Broke the World

Okay maybe you've read it but PROBABLY not...

Human beings are a strange lot. We are a people of words—and words committed to ink have a way of starting revolutions.

People have spilled blood over spilled ink for millennia. The Communist Manifesto toppled empires. Common Sense birthed a nation. Uncle Tom's Cabin called that same nation to account for its sins. Darwin's Origin of Species rewrote people’s understanding of themselves. Locke's Two Treatises redefined government.

But there's another book—or rather, a commentary on a much smaller book—written by a tormented German monk in the 16th century that helped fundamentally rewire the intellectual DNA of Western civilization. While it didn't single-handedly create modern freedom, it provided crucial intellectual foundations that made later developments in democracy and individual rights possible.

The book is Martin Luther's Commentary on Galatians, and you've probably never heard of it.

Which is strange, because it helped create the world where you can think for yourself.

The World Luther Inherited

To understand why this commentary became so influential, you have to understand the world Luther was born into—a world where the Catholic Church wielded enormous spiritual, political, and economic power.

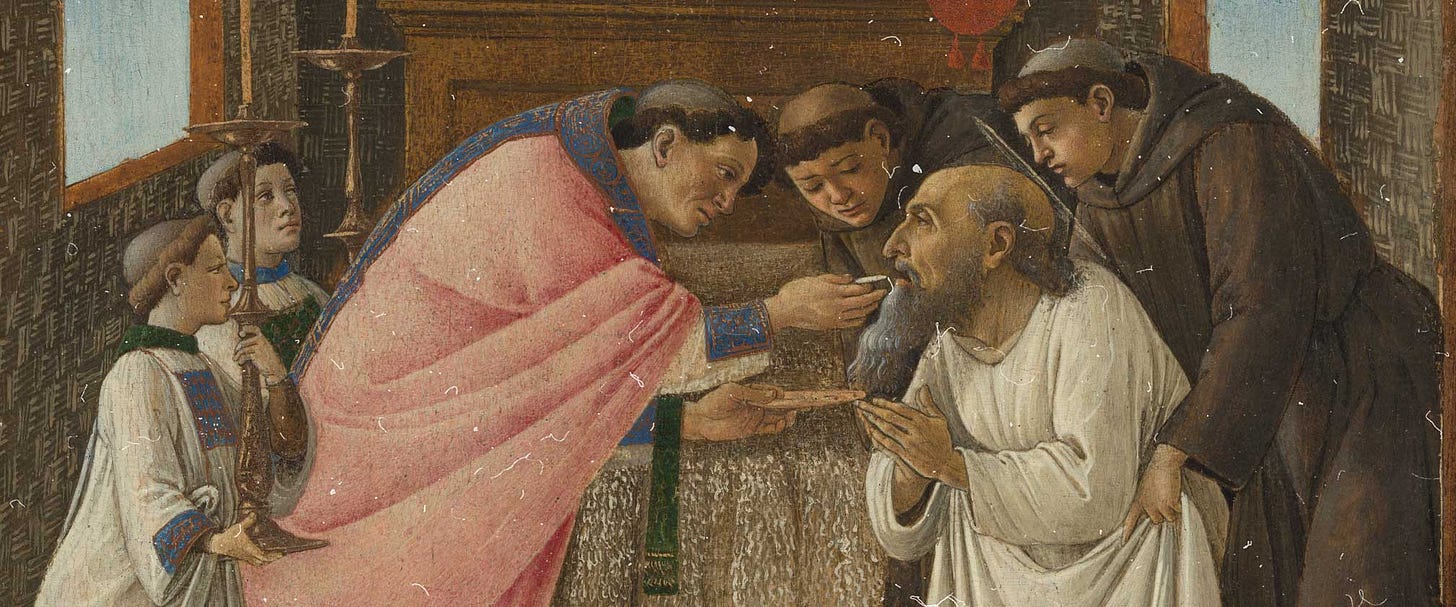

Late medieval Europe operated on what we might call "spiritual monopoly." The Church positioned itself as the primary mediator between God and humanity, the dispenser of grace, the authoritative interpreter of salvation. This wasn't just theology—it was institutional control on a massive scale.

The system worked like this: The Church taught that salvation required both faith and good works, with the Church largely defining what those works entailed. You needed to confess to a priest, participate in sacraments, and—increasingly—pay for indulgences. These were literally payments for forgiveness, often sold with promises of reduced time in purgatory for yourself or deceased relatives.

By Luther's time, indulgences had become a significant revenue source for Rome. The most notorious example was Johann Tetzel's sales campaign in Germany, with his infamous jingle: "As soon as the coin in the coffer rings, the soul from purgatory springs."

This system made the Church enormously wealthy and politically powerful. But it also created what Luther would come to see as spiritual tyranny—a mediated relationship with God that could be manipulated, controlled, and monetized.

Luther, an Augustinian monk struggling with intense spiritual anxiety about his own salvation, began questioning this system not out of rebellion, but out of desperate personal need for certainty about God's grace.

The Letter That Changed Everything

Luther found his answer in Paul's letter to the Galatians—a passionate epistle written to early Christians who were being told they needed to follow Jewish ceremonial law in addition to faith in Christ to be truly saved.

The letter to the Galatians reads like a first-century theological manifesto: "You foolish Galatians! Who has bewitched you?" He argued that requiring anything beyond faith in Christ was not just wrong—it perverted the central message of Jesus himself.

For Luther, reading Galatians was like discovering a different universe. He realized that the entire late medieval system—with its emphasis on earning salvation through works, payments, and institutional mediation—contradicted Paul's central message about the gratuitous nature of divine grace.

This insight led Luther to articulate principles that would prove historically explosive:

Sola fide (faith alone): Justification comes through faith, not through works or institutional mediation.

Sola scriptura (scripture alone): The Bible, not Church tradition or papal decree, is the ultimate religious authority.

These weren't just theological positions—they challenged the fundamental basis of medieval Church authority.

The Commentary That Shook Foundations

Luther's Commentary on Galatians was actually written twice—first as lectures in 1519, then expanded into the influential lectures in 1531 that became the 1535 version we know today. By then, the Reformation was well underway, and Luther was working out the full implications of his earlier discoveries.

"The world bears the Gospel a grudge," Luther wrote, "because the Gospel condemns the religious wisdom of the world." He was arguing that institutional Christianity had become precisely what Paul opposed in Galatians: a system that placed human requirements between people and divine grace.

Luther originally intended to reform the Church, not split it—hence "Reformation." But ideas have consequences beyond their creator's intentions. Once Luther established that ultimate spiritual authority resided in Scripture rather than institutions, and that individual conscience could access divine truth directly, he had created intellectual foundations that would eventually extend far beyond religion.

Consider this crucial passage:

"Whether a servant performs his duties well; whether those who are in authority govern wisely; whether a man marries, provides for his family, and is an honest citizen; whether a woman is chaste, obedient to her husband, and a good mother: all these advantages do not qualify a person for salvation. These virtues are commendable, of course; but they do not count points for justification."

Luther was arguing that ultimate human worth before God doesn't derive from social position, moral performance, or institutional approval. It comes from divine grace—something no earthly authority can control or dispense.

The implications were staggering. If your fundamental dignity doesn't depend on your position in social hierarchies, then those hierarchies lose their claim to divine sanction. If individual conscience has direct access to ultimate truth, then human authorities become provisional, questionable, reformable.

When forced to choose between competing authorities, Luther was uncompromising: "It seems we must choose between Christ and the Pope. Let the Pope perish."

"But I'm Not Religious—What Does This Have to Do With Me?"

Here's why this 500-year-old theological argument matters to all readers — secular and religious alike: Luther's insights about conscience, authority, grace, forgiveness, salvation, and human dignity helped create the intellectual conditions where Enlightenment political theory could eventually flourish.

The ideas that grew from Luther's work about individual conscience and direct access to truth contributed to several crucial developments:

Political participation: If individuals could interpret Scripture for themselves, the concept of self-governance became more plausible. Protestant emphasis on individual conscience provided one foundation for later democratic theory.

Economic mobility: If work was a divine calling rather than fixed social destiny, then social hierarchy became less rigid. The "Protestant work ethic" had political as well as religious implications.

Educational expansion: If every person needed to read Scripture, then literacy became essential. Protestant regions did indeed become among the most educated in Europe.

Religious tolerance: If conscience was individual and direct, then religious coercion became harder to justify. The concept of religious freedom had Lutheran roots, though it took centuries to fully develop. (It is important to note that Luther endorsed no such concept as religious freedom — this came much later.)

Now, I'm not arguing that Luther's commentary single-handedly created modern democracy. Other intellectual traditions—classical republicanism, Renaissance humanism, Enlightenment rationalism—also contributed essential elements. Thinkers like Locke, Montesquieu, and Rousseau built crucial bridges between Protestant theology and political theory.

But Luther's work helped create the conceptual space where these later developments could take root and flourish. It was one crucial ingredient in the complex recipe that eventually produced modern notions of individual rights and democratic governance.

The intellectual line from Luther's emphasis on individual conscience to Jefferson's "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness" runs through many way-stations, but it is historically traceable. Both rest on assumptions about human dignity that transcend social position—dignity that comes from above human institutions rather than through them.

Why You Should Read This Book (Even If You're Not Religious)

Luther was deeply flawed. His later anti-Semitic writings were vicious and inexcusable. His views on women, social hierarchy, and peasant rebellion were often reactionary. He was horrified when radical reformers used his ideas to justify social revolution, and he remained quite conservative on many political questions.

I'm not asking you to embrace Luther the man, but to encounter Luther the pivotal thinker.

His Commentary on Galatians remains one of history's most powerful statements about the relationship between individual conscience and institutional authority. It argues that human worth doesn't depend on performance, position, or payment to those in power. It insists that individual conscience, properly formed, can access truths that no institution can monopolize.

"Hereby we may understand that God, of His special grace, maketh the teachers of the gospel subject to the Cross, and to all kinds of afflictions, for the salvation of themselves and of the people; for otherwise they could by no means beat down this beast which is called vain-glory."

These insights don't require religious belief to be transformative. They require only recognition that human beings possess inherent dignity that no earthly power can grant or revoke.

Cards on the table — I am a Christian, and Luther’s writings have had profound spiritual impact on my life. The free gift of grace in Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection (yes I believe in that), continues to make up the bedrock of my intellectual and spiritual life. So I believe this commentary has special value for those who claim to follow the teachings of Jesus in any capacity.

The Book That Keeps Breaking Worlds

Luther's Commentary on Galatians helped change the world once. In the right hands, it might help do so again.

Because once you understand where human dignity actually comes from — once you understand grace bestowed over grace earned — you can never see human authority quite the same way. And that shift in perspective, however it happens, is exactly what the world needs.

This is the kind of transformative reading I want to keep exploring in these articles. Shining a light on books that won’t make BookTok, that the algorithm won’t feed you, that won’t appear on many (if any) “Summer Reads” lists.

If you want in the loop on that — subscribe.

Thank you for this recommendation

I'm so happy I subscribed!

I was looking for articles about books that are more then another commentary on new best selling romance (even though I respect and enjoy all genres) but this here is what reading is about for me. Thank you and please keep up the amazing job you are doing 👏🏻